侘び寂びとは? — フィールドワークレポート

フィールドワークレポート DAY 1

2020/12/9

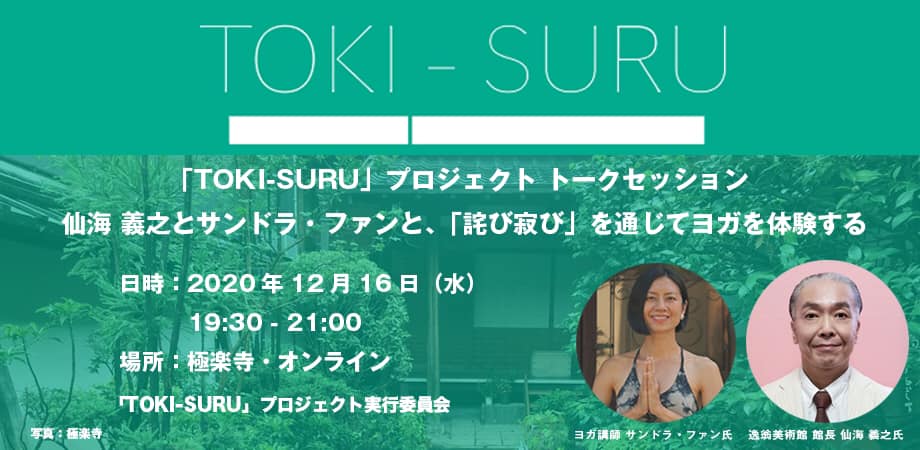

数週間前、美術手帖さんからTOKI-SURUプロジェクトへの招待をいただきました。TOKI-SURUプロジェクトとは、加速化する現代生活においてリラックスやイノベーティブな時間を創出する方法を探るための、リサーチ・プロジェクト。今回、侘び寂びとヨガのコンセプトの組み合わせを考え出されました。私は侘び寂びの意味を探り、また侘び寂びとヨガの共通点を見出すため、2日間のフィールドワークに招いていただき、そしてその締めくくりとしてヨガのワークショップを行います。

このお誘いを受けた時、私は嬉しくて天にも昇るような気持ちでした。日本で最も名高いアートマガジンである美術手帖さん、そして美術館の館長さんとの2日間のフィールドワークを過ごせて、お給料までいただける?私にこんな素晴らしい機会をいただけるなんて!と、興奮し、光栄に思い、さらに恐れ多く感じながら、すぐにそのプロジェクトに飛びつきました。

フィールドワークの初日、逸翁美術館館長の仙海さんに従い、侘び寂びの要素を探し求めて龍安寺と下鴨神社を訪れました。

Wabi-Sabi Field Work Report Day 1

Dec 9th, 2020

A few weeks ago, I received an invitation from Bijutsutecho to join their TOKI-SURU project, which is a research project aims to find innovative ways to help busy people to slow down and to find a sense of ease in our face-paced modern world. They thought about bringing together the concept of wabi-sari and yoga. I was invited to join their two-day fieldwork in search of the meaning of wabi-sabi, and to find the similarities between wabi-sabi and yoga, at the end, give a yoga class in the workshop.

I was over the moon when I received that invitation. Bijutsutecho is the most prestigious art magazine in Japan, and I get paid to spend two days on a fieldwork with the director of an art museum? What have I done in my life to deserve this opportunity? I immediately jumped on the project, feeling excited, honored, yet humbled.On the first day of the fieldwork, we followed Mr. Senkai, the director of Itsuo Art Museum to Ryoanji, shimogamo shrine in search of the elements of wabi-sabi.

侘び寂びとは何かという公式な定義はなく、日本の人に尋ねてもその意味の説明はとても難しく感じ、それぞれの人が違った答えをするかもしれません。ですが侘び寂びとはシンプルに言うと、不完全で非永久的なものに美を見い出す日本人の美意識なのです。

龍安寺は侘び寂びの素晴らしい一例です。

There is no official definition for wabi-sabi, and if you ask the Japanese people about it, most people find it hard to explain what it means, and different people may give you different answers. But simply put, wabi-sabi is the Japanese aesthetic awareness of seeing beauty in things that are imperfect and impermanent.

Ryoanji is a great example of wabi-sabi.

まず第一に長方形の庭の造形はシンプルで、15個の岩は自然のままの姿を残しています。岩の配置に対称性はありません。

次に岩の集まり同士のスペースは極めて計算なくランダムなように見えて、しかし観賞者がどこに立ってみても、常に一つの岩が隠れるように巧みに配置されています。これは私たち人間に完璧な人はおらず、私たちの限られた視点から全ての岩を観ることはできない、と言うことを暗喩しています。

三つ目に、龍安寺の壁は泥となたね油を混ぜて作られ、褐色を帯させることで錆びて見せ、老朽感、そして非永久性を醸し出しています。

First of all, the rectangular shape of the garden is simple, the 15 rocks in the garden remained their original natural shapes. There’s no symmetry in the placement of the rocks.

Second, the spaces between the clusters of the rocks seem quite random and without calculation, yet they are cleverly arranged in a way that there is always one that’s hidden from the view, no matter where the viewer stands. It implies that no human being is perfect, so we are unable to see all the rocks due to our limited perspective.

Third, the wall of Ryoanji is made of clay mixed with rapeseed oil, giving the wall a brown-is orange color that looks rusted, a hint of its old age and hence its impermanence.

仙海さんは侘び寂びとは私たちの心の鏡である、と言いました。なぜなら人間は皆不完全で非永久であるからです。それに気づくことで、私たちはもっと私たち自身に慈悲を持ち、そのままの私たち自身を包容することができるのです。

ということは、侘び寂びとは美意識だけでなく、哲学でもあるのです!ヨガのように、自分自身の内なる旅です。人生の中でのアップダウンを観察し、強みと弱み、明るい面とそうでない面を認識します。その上で自分らしさ、不完全さと非永久性、それをどのように包み込むかを学ぶのです。

Mr. Senkai said, wabi-sabi is a reflection of our hearts, because we are all imperfect and impermanent. By realizing that, we become more compassionate towards ourselves and we are able to embrace who we are.

Oh, so wabi-sabi is not just an aesthetic concept, it’s philosophy! Like yoga, it’s a journey to the self. We observe our ups and downs in life, we recognize our strengths and weaknesses, our bright side and no-so-bright side. And yet, we learn how to embrace all that we are, our imperfection and impermanence.

フィールドワークレポートDAY 2

侘び寂びの歴史は仏教そして茶道と密接に紐づいています。

茶道は僧侶たちが長時間にわたる禅の瞑想の修行の際、眠気覚ましとして始めたことに起源を持ちます。千利休は日本で現代の茶道の父として評されています。彼は中国から輸入した完璧な造りの華々しい茶器を用いる代わりに、農民の生活の中にもありふれたような器をそのまま使ったのです。

彼はまた、無駄を最小限に抑えて茶を点てる質素でありながら優雅な動きを創り出し、その茶道の所作を成文化しました。

Wabi-Sabi Field Work Report Day 2

Wabi-sabi’s history is intimately linked with Buddhism and tea ceremony. The tea ceremony has originated as a way for monks to stay awake in order to practice long periods of zen meditation. Sen no Rikyu is respected in Japan as the father of the modern tea ceremony. Instead of using the perfectly made flashy tea utensils imported from China, he used bowls that are directly taken from peasant environments. He also codified the movements of the tea ceremony, creating economical and graceful movements of making tea with a minimum fuss.

ヨガの哲学にサントーシャというものがあります。自身のエゴや欲望を満たす材料を外に求めるのではなく、内側から満ち足りていることを自分の中に見出します。正に茶道の無駄がなく優雅な所作のように、ヨガのアーサナは身体の安定性とマインドフルな安らぎの感覚の中で練習されます。

フィールドワークの二日目に、「土楽」さんの陶芸家福森さんを滋賀の伊賀に訪ねて行きました。福森さんは土鍋と茶器で有名です。豊かな自然に囲まれた滋賀の田舎で作業場とギャラリーを自宅の隣に構え、伝統的な日本家屋で暮らしておられます。

私たちは居間にある囲炉裏を囲んでの集まりに招いていただきました。部屋の中を見回すと花器から壁にかけられた絵画まで、全ての物に古びた跡や色を感じました。しかしながらほこりのない表面に主の手入れが表れていました。

In yoga philosophy, there’s a term called santosha. Instead of looking outward for materials to feed our egos and desires, we look inward to find contentment from within. Just like the economical and graceful movements in tea ceremony, the yoga asanas are practiced with physical stability and a sense of ease in a mindful way.

On the second day of our fieldwork, we traveled to Iga, Shiga to visit a ceramist at Doraku, Mr. Fukumori. He’s famous for his clay pots and tea utensils. He lives in a traditional Japanese house, and his work studio and gallery are just right beside the house, surrounded by the rich nature in the countryside in Shiga prefecture.

We were invited to gather around the irori in the living room. Looking around the room, everything from the flower vase to the painting on the wall all bear the colors and marks of age. However, the dustless surface reveals the care by their owners.

お茶をいただいた後、私たちは福森さんに単刀直入に侘び寂びの意味とは、と尋ねました。彼は私たちの目をじっと見、説明に気が進まないように見えました。「侘び寂びとは何か、と一度定義を下してしまえば、もはやそれは侘び寂びではなくなってしまうでしょう。」と言いました。

答えを求めてきた私たちは、もちろん満足ではありませんでした。侘び寂びのある何かを作り出そうという意図はない、と彼は続けました。ひとたび物が作り出されれば、侘び寂びの要素が人との相互作用で育まれ始める。物の魂は時間とその物の歩む物語によって次第に豊かになっていく。人がその物に魂を込め、時が経つにつれその物が命を持つ。

After being served tea, we went straight to the topic and asked Mr. Fukumori, what is the meaning of wabi-sabi. He looked at us into the eyes and was reluctant to explain. He said, “once you give it a definition, then it’s no longer what it is.”

Coming for an answer, of course we were not satisfied. He continued to say, he has no intention to create something wabi-sabi. Once the object is created, the element of wabi-sabi then starts to grow as people interact with it. The object’s soul is slowly enriched by the time and its stories. As time passes, the object is alive as people pour souls into it.

私は受け取ったお茶の器を眺め始めました。全ての器が違った形、色、質感でした。福森さんの使っている器には割れを直した跡がいくつかありました。ここにある器は全て彼が作ったものだと福森さんは話していました。彼の使っている器は一度お孫さんが小さかった頃に壊されたそうです。今はお孫さんは皆さん成長され、東京で働いておられます。

そして私は侘び寂びとは人が想いを注ぎ、魂を込めた物の美しさなのだと気づきました。物はそれに関わる人と共に時を重ね、その人と物の絆が、温かく安らぐ侘び寂びの感覚を生み出すのです。

I started to observe the bowls of tea that we were served. All of the bowls are different in shapes, colors, and textures. The one that Mr. Fukumori uses has a few mended cracks. He said that all the bowls here are made by himself. The one he uses was once broken by his grandson when he was little. Now his grandchildren are all grown-ups and are working in Tokyo.

Now I realize, wabi-sabi is the beauty of an object when people pour love and souls into it. The object grows old with the people interact with it, and the bond between man and the objects creates this warm and comforting feeling of wabi-sabi.

侘び寂びと関係があるか、それはわからないのですが、心に強く残って忘れられない福森さんの言葉があります。「良いことも悪いことも、私にとってはどちらも同じことです。」

I don’t kow if it has to do with wabi-sabi, but something Mr. Fukumori said to us really sticks to my mind, “Good things and bad things, it’s all the same to me.”